Recent Forum Topics › Forums › The Rams Huddle › SI: How QBs Goff, Wentz and Lynch got drafted

- This topic has 1 reply, 2 voices, and was last updated 9 years, 10 months ago by

InvaderRam.

InvaderRam.

-

AuthorPosts

-

May 3, 2016 at 8:17 pm #43357

znModerator

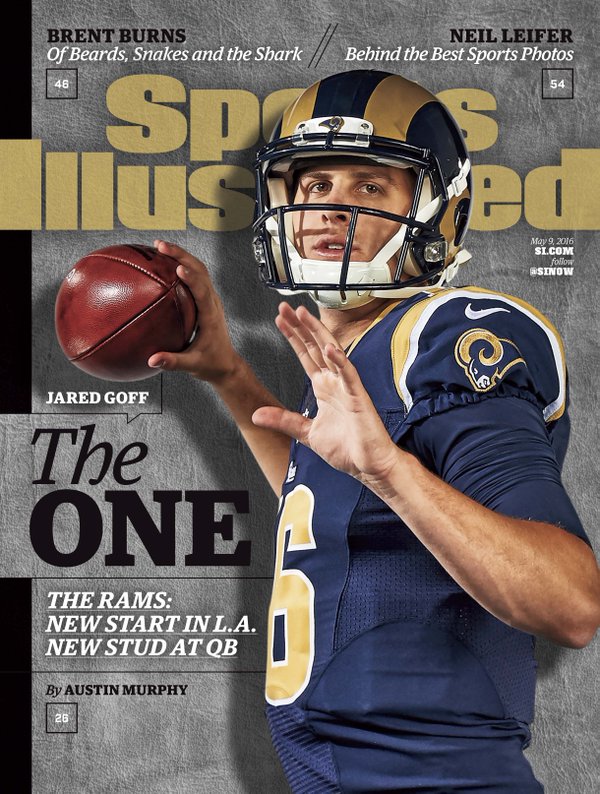

znModeratorHow QBs Goff, Wentz and Lynch got drafted

Austin Murphy

http://www.si.com/nfl/2016/05/03/nfl-draft-jared-goff-carson-wentz-paxton-lynch-first-round

It was as if Paxton Lynch knew something. The genial and power-forward-sized quarterback out of Memphis politely declined the NFL’s invitation to spend the first night of the draft in the Green Room at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, choosing instead to throw a draft/bowling party for himself and roughly 100 friends and relatives at the AMF Deltona Lanes in Orange City, Fla. “Because that’s how we roll,” wisecracked his agent, Leigh Steinberg, unable to help himself.

Time spent under the hot lights and probing TV cameras of the Green Room “is not real time,” observes Steinberg, who knew that his client was likely to go late in the first round, if he went in the first at all: “It’s water-torture time. Drip. Drip. Drip.” Instead of dying a little on the inside each time his name wasn’t called, Lynch threw strikes and gutters with his buddies until his new BFF, John Elway, reached out. True, Lynch came off the board two dozen picks after quarterbacks Jared Goff and Carson Wentz, selected first and second, respectively. But with the Broncos, Lynch finds himself, arguably, in a better situation than either of them.

Between the slow-motion free fall of Myles Jack and the impromptu drama we’ll call Tunsil Agonistes, the vibe in the Green Room was heavier than usual this year. Refuge could be taken in a nearby lounge, which the NFL had converted into a kind of speed-dating venue where draftees could knock out multiple interviews in a short time. There, at one point, was Wentz, sitting kitty-corner to his friend and training partner Goff, whom the Rams had taken. Both quarterbacks endured their debriefings with good humor, though Wentz betrayed a trace of annoyance when asked to share his thoughts on Sam Bradford, Philadelphia’s disgruntled incumbent QB.

“I’ve been an Eagle for about an hour,” the rookie replied, “so let’s wait and see what transpires.”

Laremy Tunsil’s Draft Night from Hell reminds us that the presence of a gas mask always has the effect of making proceedings more sinister and macabre. (See Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet.) It also reminds us that with its Reefer Madness attitude toward marijuana, the NFL remains stuck in the 1950s. In other ways, though, the league’s evolution continues apace. A month ago Tunsil sat atop most mock drafts. Goff and Wentz leapfrogged the left tackle—and other higher-rated players at other positions—because the league’s overlords believe that its long-term success is tethered to the forward pass.

Early in Raising Arizona the irascible owner of a furniture store berates an employee: “Eight hundred leaf tables and no chairs? You can’t sell leaf tables and no chairs. Chairs, you got a dinette set. No chairs, you got d—!” The Rams have been one chair short of a dinette since Week 7 of the 2013 season, when Bradford suffered the first of two left-ACL tears. Coach Jeff Fisher has sent out a series of well-meaning field generals—Kellen Clemens, Shaun Hill, Austin Davis, Nick Foles, Case Keenum—whose enthusiasm exceeded their talent. As GM Les Snead put it last week with bracing candor, “We’ve been a haven for backups.”

Bradford, for his part, has played well at times for the Eagles, who traded for him before last season. Just not well enough to keep Philly from spending $21 million to sign free agent Chase Daniel and then vaulting six places in the draft, from 8 to 2, for the right to pick Wentz. Bold as that move was, the Eagles’ trade-up paled in comparison with the Rams’ Beamonesque leap from No. 15 to No. 1.

Thus will this draft be remembered for the indelible image of a prospect in a gas mask and for the huge risks taken by a pair of teams determined to find just the right chair.

***

“When I’m playing,” Goff says, “I don’t really feel pressure.”

A week before Goodell called his name, Goff was sifting through a stack of pictures in the poolroom of his family’s home in Novato, Calif. One in particular made him smile.

In the photo five-year-old Jared is sitting beside his father, Jerry, in the front car of the Giant Dipper, a renowned roller-coaster on the boardwalk in Santa Cruz. Jerry is grinning; Jared’s face is contorted by equal parts anger and fear.

“He said, ‘You have to go on the Giant Dipper,’” Jared remembers. “I said, ‘Dad, I don’t want to.’ He’s like, ‘No, you’re doing it.’

“I did not like roller-coasters.”

Jerry was a star athlete at nearby San Rafael High, where he met his future wife, Nancy. He played baseball (and a single season of football) at Cal. He was drafted by the Mariners and spent parts of six seasons as a backup catcher for the Expos, Pirates and Astros. Having a former big leaguer as a father helped Jared keep his success in perspective as one of the most talented young athletes in Marin County. When he got to ninth grade, many of his friends enrolled at Marin Catholic. Jared wanted to join them. Jerry pointed out that the Wildcats’ highly regarded coach, Ken Peralta, ran a double wing offense. “You realize you’re gonna throw the ball about four times a game,” Jerry warned his son.

Jared didn’t care. He wanted to be with his friends.

As it happened, Peralta was replaced after Jared’s freshman season by Mazi Moayed, whose pass-happy spread attack took maximum advantage of Jared’s gifts. In three seasons as a starter he threw for 7,687 yards and 93 touchdowns. Having lost four games in high school, Goff’s first season in Berkeley came as a shock to his system.

Marin County is more of a hotbed of water polo and fútbol than football. Lightly recruited out of high school, the 6’ 4″, 190-pound Goff accepted a scholarship offer from then Cal coach Jeff Tedford, who was soon fired following a 3–9 season. He was replaced by Sonny Dykes. Remarkably Goff won the starting QB job out of training camp, the first true freshman to have done so in program history. In his first collegiate start he faced a Northwestern team ranked 22nd in the country. Looking on from the stands was Ryan Tollner, a former Cal reserve quarterback and the cofounder of Rep1, a sports agency whose clients include Ben Roethlisberger, Blake Bortles, Marcus Mariota and—starting this season—Goff and Wentz.

“What stood out to me was how unflappable he was,” recalls Tollner. “He just hung in there, taking shots—they blitzed him repeatedly—making throw after throw. He was running an up-tempo offense without appearing to play at a high tempo.”

Goff threw for 450 yards in a 44–30 loss. The Bears then lost 10 of their remaining 11 games, few by narrow margins. Those months of futility “never changed the way he prepared or worked, never really changed his demeanor much either,” says Dykes. “For an 18-year-old kid it was pretty impressive.”

Cal won five games the following season. Last year the Bears opened with five straight wins and finished 8–5. Having turned the program around, setting 26 school records in the process, Goff declared for the draft. Scouts were taken with his supreme accuracy and quick, compact release. NFL personnel types also rave about Goff’s sweet feet: his innate ability to shuffle, slide, step up and otherwise buy time in the pocket. He does all this while projecting the cool of his boyhood idol, Joe Montana.

“When I’m playing,” Goff says, “I don’t really feel pressure.”

Tollner puts it this way: “Certain guys don’t process the consequences of failure the way everybody else does. He’s one of those guys.”

The resilience Goff displayed during the forced march of his freshman season would serve him well, it was speculated, with his first NFL team—especially if it were the Browns. While the Titans, owners of the first pick, weren’t in the market for a QB (they drafted Mariota last year), Cleveland, holding the second selection, most definitely was. Based on his conversations with the Browns’ first-year coach, Hue Jackson—who happened to have been Tollner’s position coach at Cal—the agent was “extremely confident” that Cleveland would go with Goff.

That was in January, before the world found out about Wentz.

***

If Goff is the Natural, as Tollner refers to him, Wentz is the Prototype. At 6’ 5″, 237, he’s got 20 pounds on Goff, as strong an arm and more foot speed. The pride of Bismarck, N.D., has spent far more time than Goff under center, running coach Chris Klieman’s pro-style offense at North Dakota State. Wentz’s game tape overflows with Wow! throws. Sure, scouts would’ve liked to see him completing those passes against, say, Alabama, rather than Weber State and Western Illinois. But at a certain point a throw speaks for itself.

Wentz secured legendary status in North Dakota in January when he led the Bison to their fifth straight FCS championship, 11 weeks after having surgery on his broken right wrist. He could’ve bailed on the team to be fully healed in time for the NFL combine. Instead, his loyalty and grit sparked a dramatic rise in his stock, which continued to soar at the Senior Bowl. Says Howie Roseman, the Eagles’ executive VP of football ops, “I was struck by the presence he had, the leadership he showed in a setting with all sorts of guys from bigger schools.”

By the time the combine rolled around in late February, Wentz had pulled slightly ahead of Goff in most mock drafts. It didn’t help Goff that in the all-important rubric of hand size—we are only half-joking—his mitts measured nine inches from thumb to pinkie. Anything less would’ve been a red flag to teams worried about his ability to hold and throw a wet ball.

Count the Browns among the worrywarts. At the end of Goff’s Pro Day on March 18, Cleveland associate head coach Pep Hamilton had him throw a half-dozen balls that had been doused with a water bottle. Goff threw ropes, easily passing the test. (“I don’t know if you noticed,” Goff confided last week, “but when [Hamilton] was soaking the ball, I would turn it upside down”—to keep water off the seams and his fingers.) Somehow his hands measured 9 1⁄8 inches that day. Asked to explain the disparity, Goff deadpanned that he’d used a “special measuring tape for small-handed people.”

Five teams were keenly interested in taking a QB in the first round: Cleveland at No. 2, Dallas at 4, the 49ers at 7, the Eagles at 8 and the Rams—although L.A.’s draft position, 15, made it an unlikely candidate to land either Wentz or Goff. Or so it seemed. While the Titans were linked to Tunsil for weeks, Tollner believed they would deal the top pick rather then use it on a nonquarterback. Tennessee’s first-year GM, Jon Robinson, had holes all over his roster; it made sense that he’d entertain offers.

And it made sense for the Rams to take a serious run at that No. 1 pick. They needed an upgrade at quarterback and, with their relocation from St. Louis to L.A., a new face of the franchise. They could afford to part with some draft picks this year and next; they were still living off the fat of the lopsided deal they’d cut with Washington four years ago. The team from D.C. had coughed up one second- and three first-round picks to the Rams for the right to move up to No. 2 and select Robert Griffin III.

In early March, not long after the combine, Rams GM Les Snead called Tollner. He needed to work out both Goff and Wentz “like, immediately.” Why, asked Tollner. “Because this trade’s about to happen.”

A retinue of Rams flew to Fargo, where Wentz’s workout was “excellent,” recalls Snead, though he allows that Goff “was always the leader in the clubhouse.” That night the L.A. contingent flew into Oakland, where it was pouring. Upon arriving at the Claremont Hotel, they were greeted by Goff. “We’re scheduled for a 9 a.m. workout tomorrow,” Snead told him. “It looks like rain, but there may be some pockets of dry air. Can you be flexible?”

“We’ve got a 9 a.m. appointment,” came Goff’s reply, “and I hope it’s raining.”

It drizzled at first, then poured. Goff crushed the workout. “When we got back on the plane,” recalls Rams COO Kevin Demoff, “there was this sense from Les and Jeff that they’d found their guy.”

The Titans got cold feet; the trade was postponed. It was in Rep1’s interest for some QB-hungry team to swing a deal with Tennessee. So Tollner reminded Snead that the Rams weren’t the only team working on a trade. One club in particular, he knew, was eager to trade up. But that team’s reliance on analytics, Tollner believed, would prevent it from moving higher than the fourth pick. To get from 4 to 1, Tollner told Snead, would take more than analytics.

Tollner was still asleep on the morning of April 14 when his phone vibrated: The deal was done. The Rams had parted with a raft of high picks—their first-rounder, two second-rounders and a third-rounder this year; a first and a third in 2017—for the right to this year’s No. 1 pick. When they spoke a few moments later, Tollner greeted Snead thusly:

“You have the biggest balls in the NFL.”

***

On draft night that distinction belonged more to Lynch, who was “throwin’ rocks,” as Donny puts it in The Big Lebowski, at the Deltona Lanes.

Shortly before the Jets went on the clock with the 20th pick, Steinberg summoned his client from the lanes, preparing him for his close-up, just in case. When the Jets spent the pick on Ohio State linebacker Darron Lee, Lynch wasn’t discouraged. He’d been told that the Cowboys, who had taken Buckeyes running back Ezekiel Elliott with the fourth pick, were trying to claw their way back into the first round to scoop him up; Jerry Jones was anxious to start grooming a high-end replacement for the brittle 36-year-old Tony Romo. Dallas found a willing trade partner in the Seahawks, sitting at 26. But the figurative envelope they offered to Seattle—second- and fourth-round picks—was light. Dallas was outbid by the Broncos, who were feeling a certain urgency themselves, having recently watched their supposed quarterback of the future, Brock Osweiler, bolt to the Texans.

Lynch had left the building by the time the Broncos called: He and some Tigers teammates were throwing a football around in the parking lot. Steinberg had to run outside and shout, “You just got drafted by the Denver Broncos!”

Someone handed him a phone. Elway was on the line; his greeting, by coincidence, evoked Jeffrey Lebowski: “Congratulations, dude!”

Lynch struggled to master his emotions, wiping his tears with his T-shirt. “This is what I’ve been dreaming of since I was five years old,” he explained.

It’s been three years since Lynch worked out of a huddle, he rarely called pass protections or controlled the game at the line of scrimmage, and has seldom taken a five- or seven-step drop, but the Broncos brain trust reportedly had Lynch ranked behind Wentz, but slightly ahead of Goff. That’s at least in part because Lynch, an exceptionally athletic 6’ 7″, 244 pounds, is ideal for Denver coach Gary Kubiak’s system, which emphasizes stretch plays, rollouts and play-action. That said, he’s no threat to be a starter anytime soon. “I love the kid and I believe in him,” said the NFL Network’s Mike Mayock, moments after the pick, lauded by many as the most inspired of the evening, “but he’s got a lot of work ahead of him.”

Don’t they all. As Steinberg well knows, hearing a quarterback’s name called early in the first evening of the draft is not a predictor of NFL success. His previous clients have included Akili Smith (third pick), David Klingler (sixth) and Andre Ware (seventh). It is a cruel, inexact science, and all NFL teams can hope for is to roll more strikes than gutters.

May 3, 2016 at 11:40 pm #43359 InvaderRamModerator

InvaderRamModerator

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 10 months ago by

InvaderRam.

InvaderRam.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 10 months ago by

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.